The formal inauguration of the Clacton Lifeboat Station and naming ceremony of the Albert Edward on July 10th 1878

|

|

Clacton on Sea |

|

Albert Edward

1878 - 1884

|

||

|

The formal inauguration of the Clacton Lifeboat Station and naming ceremony of the Albert Edward on July 10th 1878 |

||

The 1st Lifeboat at Clacton on Sea arrived by courtesy of the Great Eastern Railway which then only came as far as Weeley. Named the Albert Edward it was then taken to the new boathouse which was built on a site donated for the purpose at the junction of Carnarvon Road and Church Road. The Hon. Architect of the RNLI C.H.Cooke, Esq. F.R.S.,B.A., designed the boathouse. The boat supplied was 34 feet long and 8 feet 3 ins. of beam and rowed 10 oars double banked. The Ceremony of dedication was held on 10th July 1878 after the boat had been in service for a few months.

|

|

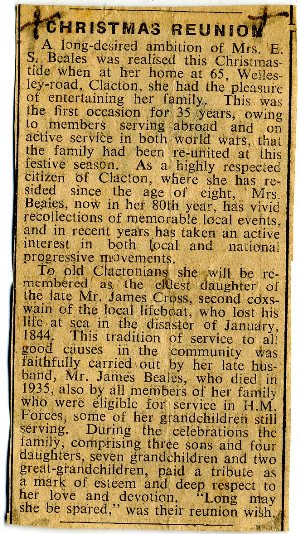

Pictured here outside the lifeboat station at Anglefield |

|||

|

|

||||

|

This rare and famous picture is of the launch of the Albert Edward on July 10th 1878 |

Details of the first active service was on 23rd May 1878.

The brig Garland laden with 500 tons of coal, bound from South Shields to London, went ashore on the Gunfleet Sands, about SSW of Clacton's Pier, in the early part of the morning. The wind was blowing hard, and although no signals of distress were hoisted by the brig (owing to her having none on board), the representatives of the local committee considered it necessary for the Lifeboat to launch to her feeling almost sure that she would not come off the sands again, and that the crew must leave her. The Albert Edward was launched at about 10am, and reached the brig about 1pm, and found her fast filling with water, and breaking up. About 3pm, the crew, 6 men and 3 boys abandoned her, and were safely landed at Clacton, at 5pm. A large number of people were on the pier, to welcome the return of the Lifeboat.

Three Lifeboats were to be provided at Clacton on Sea over the next thirty years, all named the Albert Edward, The third boat was transferred to Arranmore in 1929, and finally retired from service in 1932.

Rescue of the Schooner Ocean of Hartlepool

| Friday 14th Oct 1881 saw the one of the strongest gales in

memory, and towards the evening distress signals were seen from the direction of the

Maplin Light. The call was immediately answered by the Albert Edward at about 8pm

with the tide at half ebb. Cap. St Vincent Napean R.N., the Lifeboat Inspector for the

district was staying in Clacton at the time, and went out with the crew. The Coxswain took the Lifeboat passed several lights on his way to the Maplin Sands and eventually found the vessel requiring assistance to be the schooner Ocean of Hartlepool, bound for London with four hands, and cargo of firebricks. She had been some time on the sands, and was leaking badly. Her crew had been manning the pumps, and were completely exhausted, so the Lifeboat crew boarded her and immediately took to the pumps successfully keeping the water down. Meanwhile the Nore Light had signalled Gravesend that she had seen distress signalled, and a tug was sent out. The tug fell in with the rescue scene at 02:30am and was able to take the schooner in tow to Poplar, the Lifeboat men manning the pumps all the way. |

| On Sunday morning the Lifeboat managed to get a tow by the steamer

Glen Loch of Dundee and eventually reached Clacton pier at 4pm. She was welcomed

by a large gathering of spectators, after being away for 44 hours, her longest service to

date. Caption Napean spoke highly of the crew and the boat which responded magnificently

under very arduous conditions. As a sequel to this trip, one of the men saved from the Ocean was seen later by a police sergeant to be making off with one of the greatcoats belonging to the Lifeboat crew. He was apprehended and sentenced to one month imprisonment for his trouble. |

Rescue of the French Fishing lugger Madeline of Bologne

| The bad weather continued this dark October and on the 23rd Oct

1881 the Albert Edward was once again called out. This time the call came from

the French fishing lugger Madeline of Bologne sur Mer a vessel just four months

old. The Madeline was manned by a crew of 16 and carried 19 tons of fish 100 barrels of

salt, 300 empty barrels and mush fishing gear. She became stuck on the sands at 6:30pm but

her signals were not seen though the driving rain and low clouds until daybreak on Sunday

morning, when her last signal was very fortunately seen by the Coastguard on duty. The Lifeboat was immediately launched and the Coxswain noting the strong South Easterly wind blowing, took the Lifeboat though the Spit Way into the West Swin and hoped for a chance of a tow by a steamer into the wind. This action which was successful turned out to be the means of saving all the sixteen lives as time was paramount. The Captain and crew said that this was the most dangerous trip to date. The Madeline crew said that at the time the Lifeboat arrived she was heeled over, we were huddled together in one quarter of the deck, just out of the water, and the seas breaking completely over her. One of the Lifeboat's cables were lost and a heavy sea carried her on top of the submerged part of the wreck. This broke the Lifeboat's rudder. Several of the crew of the Madeline were hauled aboard by lifeline, one of the boys being pulled in by boathook. One man saved himself from being washed away by clutching the beard of John Greer (one of the Lifeboat crew). The steamer whose tow proved so fortuitous was named the Contest of Sunderland the crew of which praised the Lifeboat's crew. At about 1pm Sunday many people saw the lifeboat return. The shipwrecked crew were taken to the Osborne Hotel, by Mr. F.J. Nunn (Hon. Sec. local L.B. committee) the agent of the Shipwrecked Mariners Society, assisted by Messre. Morris, Dean, R.P.Shaddick, O.Davay, and others. Mrs. Price supplied the men with hot tea and a meal. The men were afterwards taken to London by rail and handed over to the care of the Consul General for France. The crew received a monetary reward and France honored the crew by the award of a gold life saving medal to the coxswain and second Cox and silver medals to the remaining crew, both coupled with a diploma. The fund for the money reward was originated by the Stock Exchange and was augmented from local sources. The presentation was made to the crew by Lady Johnson of St. Osyth Priory. The Presentation of the medals took place on the 10th Aug 1882 and the French Government requested that the occasion should be as auspicious as possible. The Lord Mayor of London was requested to present the awards, which he did in the Saloon of the Mansion House, London. The crew created a memorable occasion by appearing in their uniforms and cork jackets, and each member wearing a good sized 'button hole' handed to them by Miss Philbrick of Scarletts, Colchester, when the train stopped at Colchester station. Among the many notable people present were Sir Edward Perrott, and Adml. Ward of the RNLI The medals (with their names on the reverse side) and diplomas were then presented to the following.

Robert Legerton (coxswain) James Cross (sec Cox) Both received Gold Medals, and the following all received Silver.

William Willis Robert Osborne Charles Schofield William Schofield John Greer Richard Stockman John Austin Benjamin Addis Robert Rouse Maurice Nicholls Thomas Hobbs Unfortunately 2nd Cox James Cross drowned three years later on a rescue on the 23rd January 1884 see Night of the Disaster, while investigate flares. |

Source: The Illustrated London News, No.2254�Vol. LXXXI, Saturday, July 15, 1882, p.70

| A meeting of this institution was

held at its house, John-street, Adelphi, on Thursday week. Mr.

Lewis, the secretary, having read the minutes of the previous

meeting, it was reported that the French Government had

forwarded through the Foreign Office, a gold medal for

presentation to each of the first and second coxswains, and a

silver medal for each of the eleven men forming the crew of the

Albert Edward life-boat, belonging to the institution, stationed

at Clacton-on-Sea, on the Essex coast. This great honour had

been given in recognition of their services in rescuing, under

most perilous circumstances, the crew of the fishing lugger La

Madeleine, of Boulogne, which was lost on the Gunfleet sands on

Oct. 23 last. The Albert Edward life-boat was presented to the

Institution in 1877 by the United Grand Lodge of Freemasons of

England, in commemoration of their thankfulness at the safe

return from India of the Most Worshipful Grand Master, H.R.H

Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, and has since then saved

fifty-six lives from various wrecks. Rewards were granted to the

crews of different life-boats for their services during the past

mouth. Payments amounting to upwards of �4000 were likewise

made, on some of the life-boat establishments of the

institution. The late Henry Morgan Godwin, Esq., of Brighton,

had bequeathed �1000 to the institution. The late Mrs. Anne

Williamson, of Manghold, Isle of Man; Miss Emily Paddon, of

Brighton; Mrs. Elizabeth Jeffery, of Nottingham; and George

Cheesman, Esq., of Dorking, had also left it liberal legacies.

Reports were read from the chief inspector and the five district

inspectors of life-boats to the institution on their recent

visits to life-boat stations.

|

The Night of the Disaster

On the night of 23rd January 1884 The Lifeboat Albert Edward went out to investigate flares seen south west of the town, crossing the Wallet under close-reefed canvas and sailing right over the Gunfleet Sand. Coxswain Robert Legerton told his second coxswain, James Cross, to burn a blue light to warn other shipping of their presence and if possible to prompt a reply from the unknown ship for which they were searching.

While the blue light was being held by James Cross two or three very heavy seas struck the lifeboat, following in quick succession, one of which went into the sails and filled the boat, and she had no time to free herself as the seas flowed on so quickly, Robert Legerton said in the report which he made later to the Lifeboat Institution. "I put the helm down, but she would not answer it, she heeled over, and then turned right over to port. I called out to everybody to hold on to the boat, and not let go."

Most of them held on tight and were still on board when the lifeboat did eventually come upright again, after the coxswain had cut the sheets, which were foul, to allow the pressure of the wind on the sails to be released. But James Cross and another crew member, Tom Cattermole, had been washed away and drowned.

The second coxswain James Cross had been out in the lifeboat thirty three times and had assisted in the saving of 116 people.

Tom Cattermole was on his seventh trip.

|

|

| Photos of the medal awarded to 2nd coxswain James

Cross. Photos and information sent by Betty Moore who husband's great grandfather James Cross lost his life on the Clacton Lifeboat Albert Edward in 1884 |

|

This accident to the Clacton on Sea Lifeboat Albert Edward, costing two lives, and other serious accidents caused those who had the direction of the Institution to have further thoughts about self-righting. In 1887 it was decided that all self-righting lifeboats should be tested not only with their gear on board but also with weights representing the crew placed on the thwarts. It was also ordered that the boats should undergo these trials with sails set, but the foresheet not belayed. To increase the self-righting power of the boats the iron keel was made heavier and the end boxes were made longer, higher and wider at the top. During the 1880s other changes were made which were of great significance. In 1884 several self-righting lifeboats were built with water ballast tanks in them, thus returning to the principle of which Beaching had made use. And in the same year the new lifeboat for Clacton, to replace the Albert Edward which had overturned, was built with a centre board, the first lifeboat to be so fitted.

If anyone has anymore information on the Albert Edward I would be very pleased to hear from you

|